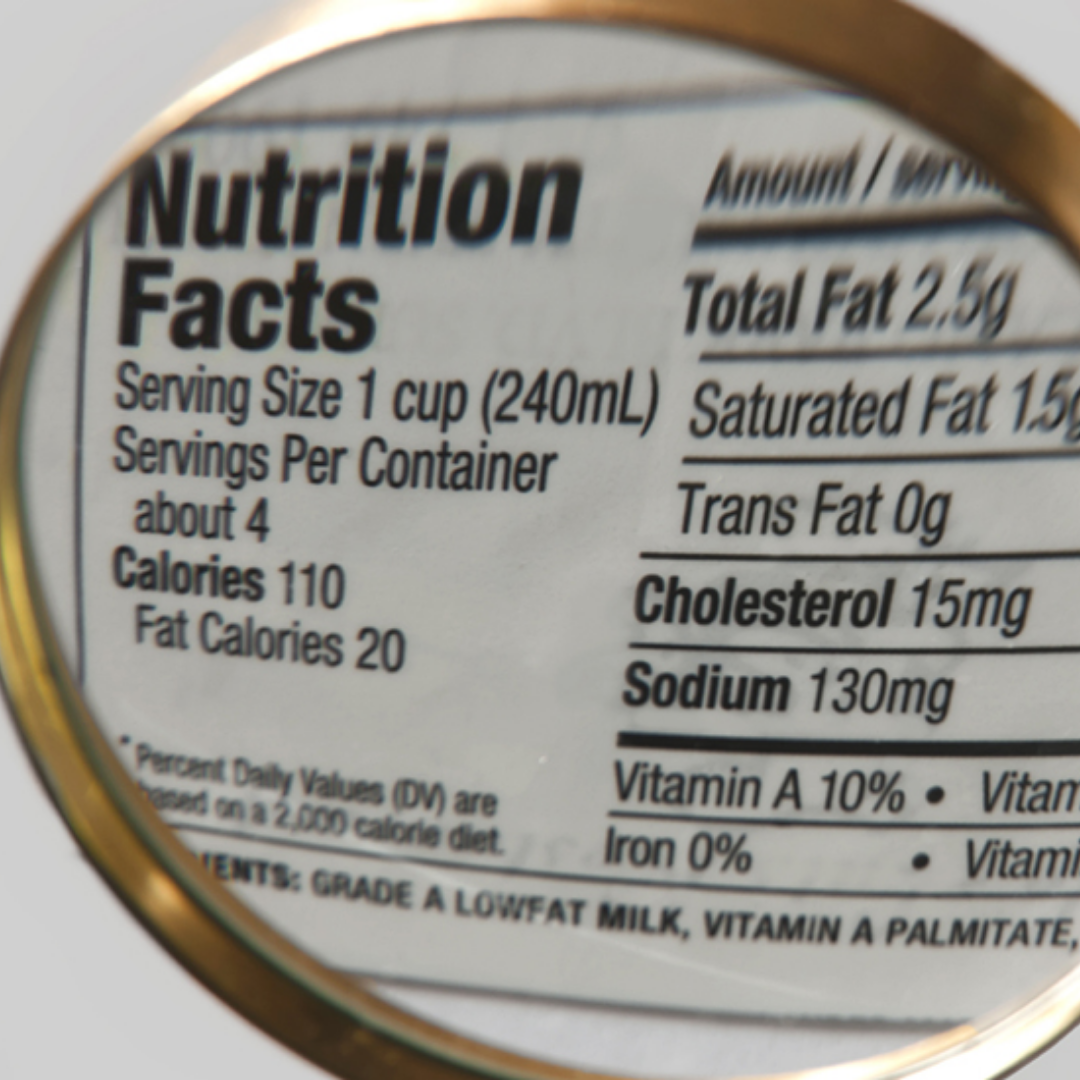

What we see and believe from reading food labels affects what we buy. Unwrapping nutrition labels can be difficult. Here are a few things you probably don’t know about the Nutrition Facts label.

Food manufacturing companies grow revenue and profit when they can effectively address evolving customer desires and deliver additional real (or perceived) value. Increasing demand for convenience food is driving significant innovation across the industry in an effort to drive growth and meet customer expectations. Products frequently target specific customer segments looking for certain food characteristics, e.g. “low-carb”, “natural”, “keto-friendly”, and “plant-based”. You’ve likely seen the increasing number of protein and nutrition bar options, cereals, crackers/chips, spreads, and other on-the-go foods being marketed to you for health, weight management, performance, or some other factor.

To help consumers to compare nutritional value between products, nutrition labels based on a standardized set of nutrition facts was implemented in 1994. They are regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Updated Nutrition Facts

Regulations around nutrition labels on foods, and legally-allowable marketing claims have arguably been behind the times for well over a decade and have not kept pace with new product innovation. In a positive step forward, this year the Nutrition Facts Label received a significant overhaul. The updated label requirements have been designed to allow consumers to make better-informed choices in the interest of public health – accounting for the linkage between diet and chronic diseases such as obesity and heart disease. You may have noticed some of the obvious changes, such as the product calories being printed in a larger and in bold font. It’s important to understand what information the labels and packaging can provide. Here are a few deeper insights about nutrition labeling of which you may not be aware.

1: Some marketing phrases legally mean something, while others don’t.

Certain marketing phrases have a defined legal meaning per the FDA and can only be used on products if they meet certain criteria.

- “Low Calorie” – no more than 40 calories for > 30g serving

- “Light/Lite” – this one can have three different meanings. 1) For foods containing more than 50% calories from fat, the light version must be reduced in fat by 50%. 2) For foods containing less than 50% calories from fat, total calories in light version should be at least 1/3 less. 3) Could mean that the light product has 50% less sodium than regular version.

- “Low-fat” – 3g or less of total fat per serving

- “Fat-free” – < 0.5g of total fat per serving

- “A good source of XX” – contains 10-19% of the Daily-Recommended-Value (DRV) in the amount that is typically consumed.

- “High in XX” – contains 20% or more of the Daily-Recommended-Value (DRV) in the amount that is typically consumed.

As you can see, a “light” version of a food does not necessarily mean it is low calorie, but it’s probably lower in calories. The FDA is serious about labels that can be misleading. For example, if a food is labeled as no sugar or zero sugar, it must also place the statement on the label “not a low-calorie food” unless it also meets that criteria. Many consumers equate sugar-free foods with being low calorie – which is often not the case.

Many other claims utilized on packaging have no standard definition, and food manufacturers need to make sure they are not running afoul of the FDA so are careful in the way they state product features.

A prime example – you won’t see packaging that explicitly states a food is “low carb”. The FDA has no standard definition on what “low” means in terms of carbohydrates. Instead, the product will highlight “Net Carbs” (total carbohydrates less dietary fiber and sugar alcohols). This is a direct math calculation from from the Nutrition Label Facts and so removes subjectivity.

Another work around is to portray a food as fitting within a type of diet plan without qualifying it, e.g. “keto-friendly” or “paleo-friendly”. These statements make no direct claims about nutritional value and benefits thus are allowable.

2: Serving sizes are larger for many foods in the recent label update.

Manufacturers must now reflect serving sizes based on the amount of food people typically consume, rather than how much they should consume. You will notice that serving sizes have grown larger. For example, a standard serving of ice cream is now 2/3 cup versus 1/2 cup.

It’s what the FDA believes is the average serving across everyone, including a 100 lb. 5’ 20-year-old female and a 250 lb. 6’ 55-year-old male. Considering this, the label serving size is not a recommendation of your portion. It’s important that you assess the right portion for you.

3: You may be getting more calories or nutrients than the package states, and there is allowable rounding.

Food companies have a lot of leeway in terms of the accuracy of their nutritional information. Calories and nutrients (including vitamins and minerals) are allowed a 20% variance. The accuracy of the information on the Nutrition Facts Label is the responsibility of the company selling the food, not the government. The FDA does go around sampling, purchasing, and analyzing products from store shelves to perform checks, but the extent and frequency of these checks is unknown.

Bottom line – it’s within legal bounds for a 200 Calorie packaged food to have 240 Calories (i.e. 200 + 20%). That being said, food manufacturers know it’s in their best interest to be a accurate as possible to keep customers happy.

The caloric value of a product containing less than 5 Calories may be expressed as zero or the nearest lower 5 Calorie increment. For example, a serving with 4 Calories can be reported as zero Calories. It’s truly rare that a food would have zero calories. Likewise, 47 calories would be rounded to 45 calories. You shouldn’t be concerned about these trace number of calories, but note they can add up if you consume a large quantity of “zero-calorie” and “low-calorie” foods.

4: The new “Added Sugars” line can be a very powerful decision-making criteria for food selection.

The new “Added Sugars” line can be immensely helpful in identifying foods that are intentionally made extra sweet to for no other reason than to be super tasty. Limit foods that have high quantities of added sugars relative to total sugar and total carbohydrates, unless you are specifically in need of a high sugar food for explicit purpose (e.g. fuel for endurance training, recovery from resistance training).

5: “Sugary” sweeteners don’t count towards “Total Sugar” or “Added Sugar” and they don’t have as many calories as typical carbohydrates.

Confused? The FDA’s assessment is based on recognition that certain sugar and sugar-like sweeteners are not metabolized by the human body in the same way as table sugar. However, they do count towards the “Total Carbohydrate” and you will often see them on a separate line item as “Sugar Alcohol”. While regular sugar is assigned 4 Calories/gram, certain other sugars and sugar alcohols are indigestible or only partially digestible and so their caloric value is assessed lower. Everyone will derive a slightly different caloric value from many of these sweeteners depending on your own ability to digest them. Here, I provide a table of common sugary substitutes as well as the FDA’s caloric assignment.

| Sweetener | Description | FDA Caloric Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Allulose | Simple sugar (epimer of fructose). Our bodies can’t effectively metabolize allulose – it’s absorbed and passed in urine. No meaningful impact on blood glucose or insulin. | 0 Cal/gr. |

| Erythritol | Sugar Alcohol. Our bodies can’t metabolize it – it’s absorbed and passed in urine. No meaningful impact on blood glucose or insulin. For some, it causes gastric distress due to fermentation in the colon. | 0 Cal/gr. |

| Mannitol Maltitol Xylitol Sorbitol | Sugar Alcohols. Our bodies can only partially metabolize them and they have a smaller impact on blood glucose and insulin versus sugar. These can also cause gastric distress due to fermentation in the colon. | 1.6-2.6 Cal/gr. |

| Hydrogenated starch hydrolysates | A mixture of sugar alcohols. Our bodies can only partially metabolize them and they have a smaller impact on blood glucose and insulin versus sugar. These can also cause gastric distress due to fermentation in the colon. | 3 Cal/gr. |

You many also see sugar alcohols marketed as a reduction in total carbohydrates for lower “net carbs” or “impact carbs”. Personally, I would not categorically call sugar alcohol-containing products “free foods.” Some of these products can still contribute a significant amount of carbohydrates.

6: Some dietary fiber has calories. Also, fiber does not have to be “natural” to be beneficial.

Soluble fiber is partially digested in our gut and is assigned 2 calories/gram. On the other hand, Insoluble fibers travel to the intestine with little change and are not digested in any meaningful way to are assigned 0 calories per gram. Both are important to our diet.

Dietary fiber that can be declared on the nutrition label includes naturally occurring fibers from plants as well as certain isolated or synthetic non-digestible soluble and insoluble carbohydrates that have been approved by the FDA. Both natural and synthetic fibers are beneficial for meeting fiber intake. You may have come across ingredients such as glucomannan, beta-glucan soluble fiber, psyllium husk, cellulose, guar gum, alginate, inulin, soluble corn fiber/resistant maltodextrin, and locust bean gum. These all count toward dietary fiber and are typically added to products to promote feelings of fullness.

Did any of this surprise you? Let me know and please forward this to friends who may find it interesting.

Need a plan and support to improve your physique, strength and energy? There’s no better time than now to invest in yourself – click here to get started.